A message from the conference organizer, Lee Novick, now Rabbi Leah Novick….

Participants at the First National Women’s Conference, Houston, 1977 write the untold history of the only federally funded conference by, for and about women.

“Houston was the overture to the great symphony of American feminism in the 20th century.

That theme has been playing out in the Congress, the State governments and the Supreme Court.

It is apparent in the media, sports, law, academia. religion and our economic life.

The genius of Congresswoman Bella Abzug and the devoted IWY commissioners was in stimulating the activism of

thousands and beyond. The women of today are anchoring in the progress launched in Houston, despite setbacks.

Thank you.” Rabbi Leah Novick, https://www.rabbileah.com/

Next…? Your thoughts here….

It all begins with an idea.

We are looking forward to hearing from Donna De Varona, Olympian and President of DAMAR, Inc. about the history of women in sports leading up to Houston, the absence of a plank on women in sports at the First National Women’s Conference, what that meant for women’s athletics after the conference, and how decades of work, including her representation on world bodies, has changed and continues to act “to reach equality not only on the field of play but behind the scenes.” See a short interview here. Thank you, Donna!

Liz Carpenter for a US postage stamp!

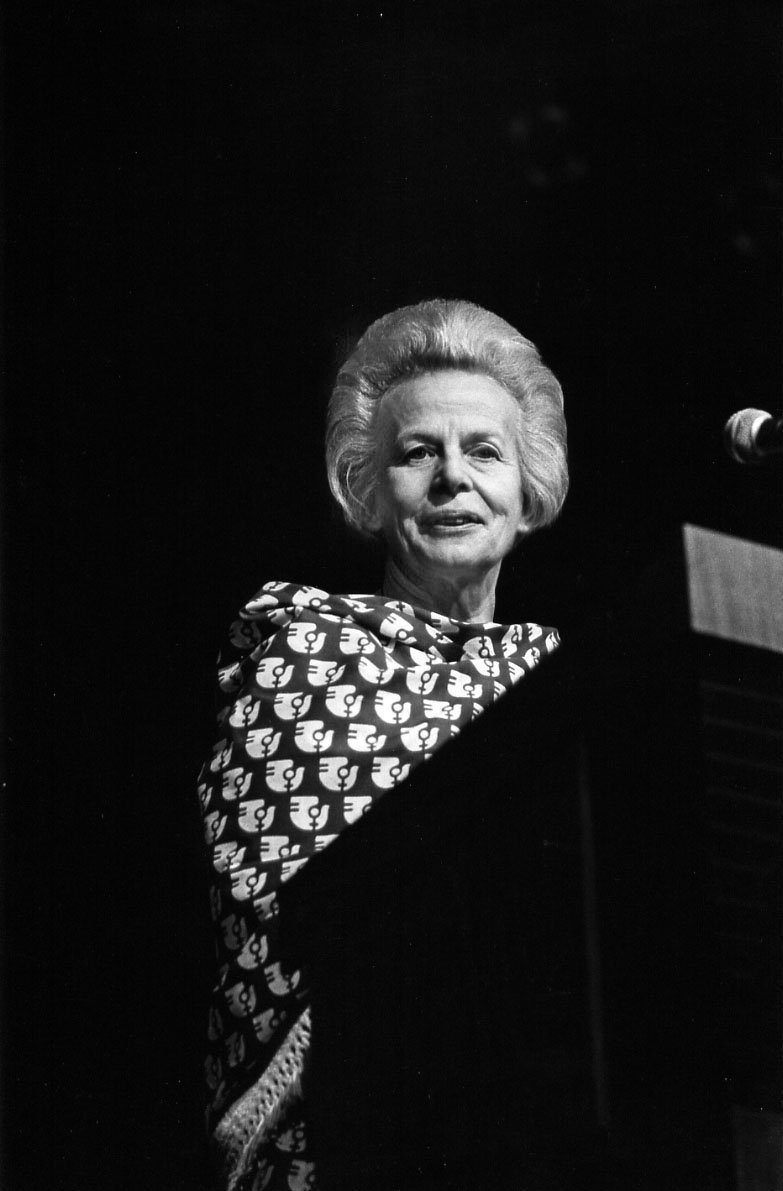

Liz Carpenter at Lincoln Center benefit for the National Women’s Political Caucus, which she co-founded in 1971. See the photo she is referring to at the article by Lucy Komisar, “with the Women at Houston” in the Works<Talent page of this website.

From: "Liz Carpenter" <lizbooks06@gmail.com>

Date: January 31, 2007 11:10:18 AM EST

What a good idea for stamps. We're tired of having to lick the good ole' boys. I love the picture you chose of me with Gloria. Let me know how I can be helpful.

Love Liz

Liz Carpenter

Austin, TX

Diana wrote back March 6,2007 (in part): “I am honored to count you among the stamp campaign’s charter supporters. The effort will receive a great forum when I speak at the Organization of American Historians’ annual meeting in Minneapolis which will also display my photographs of the First National Women’s Conference

Thank you so much for “being there” for me. You have raised my spirits and I hope that this correspondence will not put any burden on you but only reassure you that your influence is marching on! Whether I hear from you again or no, I will be thinking of you fondly and with very best regards…”

Okay, let’s do it!

Time to get those US postage stamps of women leaders of the 1970’s as portrayed by Diana Mara Henry. It’s just as good an idea as when Liz Carpenter told her: “I want to be on a postage stamp!”

Getting ready to go to Houston….Diana Mara Henry with a Halliburton case (probably borrowed from Peter B. Kaplan) and her Dior bag. Or maybe she was already there, she is wearing her badge…..

What did the official photographer look like at Houston? Here she is in the exhibit hall, signing up for some good cause! Thank you, maybe to Sherry Suris, for the photo…..

Linda Garcia Merchant

US Latino Digital Humanities Post Doctoral Fellow,

Arte Público Press at the University of Houston #usLdh

Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage

Find Recovery on Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

Chicana Diasporic: A Nomadic Journey of the Activist Exiled

Chicana Por Mi Raza Digital Memory Collective

Diana and Linda created the Sisterhood Salon at the 40th anniversary conference as a place to hang out with the women who were writing the history in visual media, text and spoken word. This website, as it turns out, is an offspring of the Sisterhood Salon…Thank you Linda, thank you all!

#BeLikeEdith

Edith May Babcock was an adventurous, independent minded woman, raised in the small West Texas town of Sonora in 1926. She chronicled and journaled her life story; childhood, falling in love and marrying, living abroad, and raising her young family in 1950’s South Africa and 1960’s South America, then suddenly becoming a single woman in the early 1970’s. She rejoined the workforce, believed in women’s rights, ran marathons, and respected people of all races from every part of the world. Always ready for the next globe-trotting experience, even into her nineties, her motto was, “I’ll go anywhere, anytime!” Her story will be an inspiration, for she was stronger than most people knew.

Her daughters Peggy and Edith send this message:

“One can make a difference, just by being what some might call an ordinary person. Facing an unexpected divorce in 1972, Edith Babcock Kokernot, at the age of 45, came face to face with the realities of her new role as a single mother, head of household in the 1970's. Like many women of that time, she encountered numerous roadblocks. But the "second wave" of women's feminism was already underway to change that; a unified front of both liberals and conservative sought equal rights for women including work, politics, family, and sexuality.

On November 18, 1977, two of Edith's daughters, Diana and Peggy Kokernot, marched with an enthusiastic crowd along with Bella Abzug, Betty Friedan, and Billie Jean King to open the National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas. Peggy was one of three torch bearers. The Houston conference helped carry the flame onward for women’s equality. Edith reflected on the events of that historic morning in her essay, The Last Mile. To learn more about Edith, her life is documented through her written works and photo gallery in her website: https://edithmaybabcock.com

That Woman: The Making of a Texas Feminist

by Nikki R Van Hightower

A founder and former executive director of the Houston Area Women’s Center. She has taught at the University of Houston, Lee College, and the Texas A&M University School of Rural Public Health. Van Hightower retired as senior lecturer in political science at Texas A&M University, where she helped establish the women’s studies program. She lives in College Station, Texas.

…….“. . . the best-known feminist in Houston”—The New York Times

When Nikki R. Van Hightower stepped into the position of Women’s Advocate for the City of Houston in 1976, she quickly discovered that she had very little real power. And when the all-male city council cut her salary to $1 a year after she spoke at a women’s rights rally, she gained full appreciation for just what she was up against.

Nonetheless, before the job was abolished altogether two years later, Van Hightower went on to help orchestrate the enormously successful 1977 US National Women’s Conference in Houston as part of the 1975 International Woman’s Year, to help found the Houston Area Women’s Center and establish its rape crisis and shelter programs, and to host a radio show where she publicly discussed issues of gender, race, and human rights.

This eye-opening memoir offers a window into the world of Texas history and politics in the 1970s, where sexual harassment was not considered discrimination, where women’s shelters did not exist, where no women were elected to city government, where women in the parks department were prohibited from working outdoors, and where women paid to use airport toilets while men did not. That world that may seem distant and slightly unreal today, so all the more reason to read Van Hightower’s journey as a feminist. Her story will remind us that while much has been achieved in gender relations and women’s rights, there is much that remains to be done.

…………………

See a video by Veteran Feminists of America with Nikki Van Hightower here. She discusses her position as the City of Houston’s Women’s Advocate and how that influenced the decision to site the First National Women’s Conference there.

October 25, 2012 [Message on the occasion of the 35th anniversary event organized by Diana Mara Henry]

Dear Participants and Friends of the 1977 IWY National Conference in Houston:

I regret that I cannot be with you, but want to share my warmest wishes for this gathering. Also, I want to share some of my thoughts on the impact of IWY on the City of Houston, the women of Houston and me, as an individual participant.

The year or so leading up to the IWY Conference was a very difficult time for me, as the Women's Advocate in the Houston Mayor's Office, and the courageous feminists who were struggling for equality and services for women. The all-male city council members at the time were fiercely hostile to the idea of a Women's Advocate and of the goals of the Women's Rights Movement. The State and local culture was not particularly friendly or well informed on the issues.

In addition to struggling for my survival in City Hall, I was also working with individuals and organizations to establish a center to provide crisis services for women and their children (domestic violence, sexual assault, discrimination, etc.), since the City lacked all such services. The challenges seemed daunting.

The IWY state and national conferences infused the Houston Women's Movement with new energy and determination. It was thrilling to meet and communicate with amazing women leaders from across the country--some we had heard of, many we had not. It brought legitimacy and credibility to our causes with written material and research on women's issues as well as the presence and/or support of Presidents, First Ladies, elected officials and the United Nations. Instead of being the brunt of jokes for our efforts for equality and services, we were, for the first time in history, center stage in the political arena.

IWY broadened our outlook, both nationally and internationally. IWY Conferences in other countries gave us opportunities to hear about the problems and challenges faced by women in other cultures. The state and Houston Conferences made us address our own misunderstandings with each other in terms of race, religion, ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation, etc. It effectively forced us out of our comfort zones, making the movement much stronger and diverse as a result.

The Conference had a wonderful confidence-building and energizing effect on those of us who lived in Houston or who were fortunate enough to attend. Although the ERA was never ratified, (a painful loss), a wide array of federal and state legislation was passed addressing equal employment, credit, fair pay, violence against women and equal educational opportunities. In Houston, we charged ahead with forming a women's Center (the Houston Area Women's Center) which provided services for sexual assault survivors, those who suffered from abuse in the home and other women who needed support and assistance. The organization now serves thousands of women and their children each year and has widespread respect of leaders and the public.

I and many others came away from the IWY Conference more knowledgeable and more invigorated to carry on our efforts toward equality. We found ourselves working in a much more positive environment. Women started gaining electoral representation. I was forever changed by the 1977 International Women's Year National Conference.

Thanks to all of you who participated. I feel so lucky to have been a part of it.

Nikki R. Van Hightower, Texas Delegate

A young man finds meaning in his research into the FNWC….

Benjamin Ortiz-Herrera is a student at UC Davis and found the memorabilia that one California delegate had donated to U Mass Amherst through the work of Diana Mara Henry and the Special Collection of her photographs at the Du Bois Library. Here is part of his journey of discovery:

“…through Stinson, I learned a lot more about the National Organization for Women, the League of Women Voters, the Battered Women Taskforce, and the push for the Equal Right Amendment.

….The 1977 National Women's Conference means a lot to me as a student majoring in History. I am an Indigenous Mexican-American living in the United States and often feel voiceless. I am in awe of the first National Women's Conference because it was such a diverse event. Where women from all different life experiences, races, ages, socioeconomic backgrounds, and political affiliations came together for one cause, to improve the conditions of women in the United States. We need to highlight diversity in movements like these to deter from retelling traditional historical narratives. History is full of ordinary people who took the initiative to improve not just their circumstances but that of their family members, friends, neighbors, and strangers. We must demonstrate who the delegates were and why they were there, what unique life experiences pushed them to participate as delegates, and how they continued to advocate for feminism after the conference.

Review of Borrowing from Our Foremothers: Reexamining the Women’s Movement through Material Culture, 1848-2017 by Amy Helene Forss. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021

From the first page of her introduction, in which Forss shares the magical moment when she handled with white gloves Alice Paul’s “shimmering” silver bracelet threaded with charms for each state that ratified the ERA, the reader is swept up in the author’s quest to reexamine the Women’s Movement from a new and refreshing point of view. Inclusive, incisive and thoughtful. Forss mined over forty collections, from the National Women’s Hall of Fame to the National Archives for Black Women’s History, private collections, the Eagle Forum archives and the Museum of London, to name just a few. “Choosing thirty unifying artifacts pertaining to foremothers of diverse race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation and gender identity remained integral to this project….because they provided tangible proof of their yesteryear historic bravery.”

Ten years in the making, conducting interviews with 99 ”living foremothers,” Forss gives the reader a breathtaking sweep of history while pinpointing the objects that symbolize the joys and pain of women’s unquenchable thirst for a society that expressed their values. Tee shirts, gavels, dresses and label pins are not merely curiosities but provide memorable access to their issues and movements that will not be easily dismissed or soon forgotten.

With its jewel of a cover, this book is a great crossover for academic and general readers. Stimulating, breezy writing and interesting historical, economic and geographic context (such as the description of the lay of the land of Seneca Falls, where the Suffragist convention organized by Susan B. Anthony took place in 1948) combine with “You are there” moments such as the tea party that cemented the bond between Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Among the 31 unforgettable illustrations, a personal favorite: twenty sketches by Valerie Pettis showing the evolution of her iconic United Nations International Women’s Year symbol from start (a delicate globe inset into the female symbol) to finish – a bold dove incorporating the female symbol in its body with the equal symbol in its wings. This seldom-seen diary of a creative process symbolizes the evolution of an idea, a commitment to representing the many strands of a dream become reality with a future, like this book itself.

A uniquely well-chosen dozen of the keystone documents of more than a century and a half of US Women’s History round out the book, from Sojourner Truth’s “Ar’n’t I a woman?” speech in 1851 -recorded by two different people who heard it -a man and a woman- to Maya Angelou’s “To Form a More Perfect Union,” the mission statement of the First National Women’s Conference in 1977 and Phyllis Schlaffly’s “God, Family and Country” delivered in Houston the same day. The E.R.A. is presented in three versions in which it was proposed to Congress, from 1923 on.

With very complete and informative endnotes, and the valuable bibliography that includes archives, manuscript and museum collections as well as convention proceedings and magazine articles by key players.

Hurry! This is THE book to offer as a gift to even your most accomplished feminist sisters and anyone who enjoys a good read with lots of touching and intriguing true stories and something new to discover on every page. – Diana Mara Henry (a foremother).